DIPLOMACY

AND INTRIGUE

DIPLOMACY

AND INTRIGUE

Confederate Relations with the Republic of Mexico, 1861-1862

by Robert Perkins

It is a little known fact that, even as its armies were attempting the conquest of the United States Territory of New Mexico, and as its politicians were debating the creation of a Territory of Arizona, the Confederate States of America was engaged in a covert attempt to wrest the northern states of Mexico from that Republic and to annex them to the new Southern nation. Had this attempt been successful, it might have changed the outcome of the war. It is this little known, but highly significant episode of the War Between the States that will be examined in this article.

Provinces of Northern Mexico whose annexation was

planned by the Confederacy, 1861-1862

Before delving into the details of Confederate espionage and intrigue in Mexico, it would be well to examine the reasons for Confederate interest in its neighbor to the South. The Confederacy in 1861 saw both potential riches to be gained in Mexico, and the opportunity to acquire, without much cost, those riches.

The riches of Mexico were of many kinds. Of course, since the days of the Spanish Conquistadors, Mexico had been a source of great mineral wealth, especially gold and silver. The mines of the northern Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora were productive, and would have been a definite asset to the new Southern nation. And Mexico had other, non-mineral riches to offer as well. At a time when the United States was beginning to impose a blockade of Southern ports, Mexico offered a virtually unblockadeable Pacific coastline with one of the finest harbors in the Western Hemisphere, at Guaymas.1 With the Union blockade thus defeated, and with the specie of Northern Mexico in its hands, the Confederacy could have imported whatever it needed to wage war. The material advantages of the Union over the Confederacy would have melted like dew beneath the morning sun.

Furthermore, it was widely believed that the Confederate annexation of northern Mexico would have led inevitably to the conquest of California as well. The advantages which the Confederacy might have gained from such an occurrence were immense. First, the flow of California gold would have been diverted from Washington to Richmond, thus reversing the relative quotations of United States and Confederate States currency. Abraham Lincoln himself considered California gold to be the "lifeblood" of the Union, and its loss to the Confederacy would have been a severe, and possibly fatal, blow to the Union war effort. Second, the conquest of California, together with the States of northern Mexico, would have given the Confederacy a Pacific coastline of over 1,500 miles, with fine harbors at several places, good shipyards, and abundant materials. There the Confederacy might have built a merchant fleet, or even a navy, free from Union interference.2

Finally, it should also be stated that at least part of Confederate interest in Mexico stemmed from a desire, on the part of some of its politicians, to gain territory for the expansion of slavery.3 This was not a new desire...indeed, slavery advocates had howled with rage when, in the wake of U.S. victory in the Mexican War (1846-48), the United States had not incorporated the whole of Mexico into the United States, rather than absorbing only the most northern tier of Mexican provinces, as was the case. In 1861 there were many Southerners (perhaps not a majority, but at the very least a highly vocal minority) who believed that the expansion of slavery into new territories would strengthen the Confederacy, and Mexico would provide those new lands.

Benito Juarez, President of Mexico

Mexico had many things to offer the Confederacy, but it is unlikely that the Confederate leadership would have attempted to take what it wanted from Mexico if that nation had been perceived as strong enough to resist. And, it just so happened that, in 1861, Mexico was in a state of chaos. After the war, Trevanion T. Teel, artillery chief of the Confederate Army of New Mexico, reported a conversation with Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley which revealed much about the Confederate leadership's perception of Mexican weakness in 1861. Teel was informed that "Juarez, the President of the Republic (so called), was then in the City of Mexico with a small army under his command, hardly sufficient to keep him in his position." Sibley believed Juarez might be willing to agree to the Confederate annexation of the northern states of Mexico, both as a means of enriching his treasury, and because he was scarcely able to control them anyway.4

And even if Juarez was not agreeable, it might not be in his power to prevent the Confederacy from doing what it would anyway. The states of northern Mexico, most notably Nuevo Leon, Chihuahua, Sonora, and Baja California, were at this time virtually independent of the central government of Mexico, being more the feudal principalities of their Governors than integral parts of the Republic of Mexico. Direct negotiations with these Governors promised to bring these provinces into the Confederate fold, regardless of what Juarez might say or do.5

Robert Toombs, Confederate Secretary of State in 1861

Thus did the Confederacy see in Mexico not only wealth to be gained, but also the opportunity to take that wealth. And it quickly acted to seize that opportunity. In May 1861, Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs dispatched one John T. Pickett to Mexico as the Minister of the Confederacy.6 Pickett was empowered to draw up a treaty of alliance between the Confederacy and Mexico, and there was some hope that this might be accomplished, as feelings in Mexico were said (whether rightly or wrongly) to be generally favorable toward the South.7 But it soon became apparent that Pickett's orders were not those of a peaceful ambassador, for immediately upon arriving he set about stirring up an independence movement at Vera Cruz. However, Pickett's efforts were not to be crowned with success, and were to create severe problems for the Confederacy in its future relations with Mexico.8

Worried United States citizens in Vera Cruz reported Pickett's activities to the State Department, and U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward threatened to occupy Sonora with Union troops. Mexican President Benito Juarez, anxious both to forestall the Union invasion and to thwart the designs of the Confederacy on his country, introduced a bill into the Mexican Congress to authorize Union soldiers to cross northern Mexico and to use the port of Guaymas. In spite of the protests of Pickett, the bill was passed by the Mexican Congress on June 20, 1861. Pickett's blustering threats of Confederate invasion served only to land him in jail, and President Jefferson Davis was forced to recall him to Richmond.9

But the damage was done. Any chance for the annexation of Mexican Territory with the consent of the Mexican government, if such chance had ever existed, was now gone forever. Pickett's successor and Confederate Minister to Mexico, Hamilton Bee of Texas, tried to mend the relationship between the Confederacy and the Juarez government, without success. Later he tried to forge a relationship with the Emperor Maximilian, and was no more successful, although that ruler feigned friendship with the Confederacy so long as it kept the United States too busy to interfere with his plans in Mexico.10

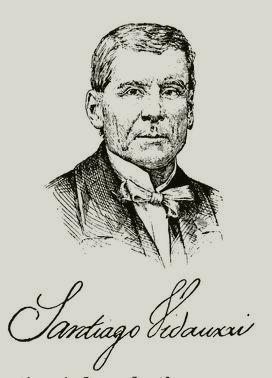

PLAYERS IN THE VIDAURRI AFFAIR

Left: Santiago Vidaurri, governor of Nuevo Leon and Coahuila

Right: Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America

The collapse of its credibility with the Mexican central government did not end the Confederacy's intrigues in Mexico. For, as mentioned earlier, there still remained the possibility of direct negotiations with the semi-independent Governors of the northern Mexican provinces. Indeed, that option presented itself soon after Pickett's departure, although, for reasons that are not entirely clear, the Confederacy did not act upon it.

In the summer of 1861, Governor Santiago Vidaurri, the feudal ruler of the provinces of Nuevo Leon and Coahuila, wrote to the Confederate Government at Richmond, offering to annex his provinces to the Confederacy in return for a regiment of Texas troops and artillery, which would be used to win a revolution. President Jefferson Davis considered it "imprudent and impolitic" to accept Vidaurri's offer at that time, but nevertheless instructed a Confederate spy in Monterey to send information about the value of Vidaurri's provinces, evidently for future reference. The strange thing is, however, that the Confederacy NEVER took up Vidaurri's offer, even at a later date. Thus, the only Mexican governor who ever expressed a serious interest in selling his provinces to the Confederacy, and certainly the only one to ever promise anything in writing, was totally ignored by the Confederate Government.11

Left: John R. Baylor, Governor of the Confederate Territory of Arizona

Right: Baylor's spy in Chihuahua and Sonora, Jose Augustin Quintero

At about the same time that President Davis was inserting a spy into Monterey, the Confederate Governor of Arizona, John Robert Baylor, was doing the same for the Mexican provinces of Sonora and Chihuahua.12 Baylor's spy (politely designated an "agent"), Jose Augustin Quintero, was an interesting character.13 He was a Cuban revolutionary who was born at Havana, Cuba, in 1829. He was educated at Harvard, but on account of the death of his father was unable to complete his course, and engaged in teaching Spanish at Cambridge, Massachusetts, until about 1850, when he returned to Cuba, and became the publisher of a newspaper at Havana. Supporting the patriotic Cuban movement of 1850-51, he was thrown in prison by the Spanish authorities and sentenced to be shot, but had the good fortune to escape from Morro Castle. Taking boat for Texas, he made his home at Richmond, Texas, studied law, and was admitted to the practice. He also obtained appointment as translator of land titles at Austin, and was thus engaged until 1859, when he went to New York city and became connected with a Spanish-American illustrated paper, edited by George D. Squires, the Illustracion-Americano. When hostilities began in 1861 he decided to cast his lot with his Texas friends, and returning to that State, enlisted at San Antonio as a privat in the Quitman Rifles, which he accompanied to Virginia. In the latter part of 1862 he was transferred to the diplomatic service, and appointed confidential agent of the Confederate States government in Mexico. It was in this capacity that he worked for Baylor. Quintero was charged with the collection and transmittal of "accurate and minute information regarding the population, area, farming potentiality, mineral resources, commercial possibilities, and the extent and state of industry" in these two northern Mexican provinces.14 It seems quite probable that Quintero's reports from Chihuahua and Sonora influenced the later decision of the Confederate authorities to open direct negotiations with the Governors of those Mexican states.

Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley

Confederate Army of New Mexico

On December 14, 1861, Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley assumed command of all Confederate forces in the Confederate Territory of Arizona, giving them a new name...The Army of New Mexico. Sibley was charged with an important mission, nothing less than the conquest of the United States Territory of New Mexico, which would then be used as a base of operations for the conquest of California, Nevada, Utah, and northern Mexico. On January 3, 1862, Sibley penned the following note to General Samuel Cooper, Adjutant and Inspector General of the Confederate Army:

GENERAL: I have the honor to report that in view of the importance of establishing satisfactory relations with the adjacent Mexican States of Chihuahua and Sonora, I have ordered Col. James Reily, Fourth Regiment Texas Mounted Volunteers, to proceed to the capitals of those States, for the purpose of delivering to their respective governors the communications which I have addressed to them, and of conferring with those officials in person upon the subjects of those communications....Colonel Reily left these headquarters for the city of Chihuahua on yesterday, the 2nd instant. The result of this mission, when known, will be promptly communicated to you.15

Sibley's aims in dispatching Colonel Reily to Chihuahua and Sonora were varied. First, he wanted to secure his southern flank by forging agreements with the Governors of those Mexican States not to allow the passage of Union troops over the territory of those States. Second, he wanted to secure the right to pursue hostile Indians into Mexican territory (an important consideration for the Confederates in Arizona, who faced an Apache enemy who thought nothing of crossing the international line to escape pursuit). Third, he wanted to purchase and store supplies in Mexico.16 And lastly, he wanted to set the groundwork for a later occupation, with the consent of the Governors, of Chihuahua and Sonora by the Confederate Army.17

Colonel James Reily

In selecting Reily for this mission, Sibley made what seemed to be an excellent choice. Reily, a Texas lawyer in civilian life, had been a member of the diplomatic corps of the old Republic of Texas. He was friendly to, and understood, the Mexican people, and was considered an able man for any mission to Mexico. Furthermore, he had been, since his teens, renowned for his skills in the art of oratory, and thus he promised to be a very persuasive negotiator. However, as one historian has pointed out, he seems to have been an "incorrigible enthusiast," who was "prone to accept half-promises as agreements, and diplomatic double-talk as indicative of progress."18 We shall see how these qualities affected his missions.

Reily arrived in the city of Chihuahua on January 8th, 1862. Taking up residence in Riddell's Hotel in that city, Reily sent a note to the Governor, Luis Terrazas, informing that official of his presence in Chihuahua and of his desire to confer with the Governor. The next morning, Reily received a note from the Governor, designating 12:00 noon that same day as the time for an interview at the Governor's palace. Reily was escorted to the palace by Don Carlos Moye (whose name is mis-spelled in Reily's report as "Moyo"), brother-in-law of the Governor and ardent supporter of the Confederacy.19

Upon arriving at the palace Reily presented Governor Terrazas with the notes with which General Sibley had entrusted him. Terrazas, upon having them translated, expressed willingness to open negotiations on the points contained in the notes (right of transit over Mexican territory for Confederate troops, and denial of that right to the Union, right of pursuit of hostile Indians into Mexican territory, and the purchase of supplies in Chihuahua for the Confederate armies).20 These negotiations were not to prove fruitful, and it would seem that Reily was mislead into believing he had achieved more than he actually had.

For example, Reily's report to General Sibley stated that the Governor had told him that "if even the assent of the President had come to him, sanctioned by the act of Congress, he did not think he would permit Federal troops to pass through the territory of Chihuahua to invade Texas." In fact, in the note sent by Terrazas to Sibley, giving the Governor's version of the negotiations, Terrazas says that he WOULD allow Federal troops to cross his territory if ordered by the Mexican Congress, for he was bound by the Mexican Constitution to do so.21

On the second point of discussion, namely the right to pursue hostile Indians into Mexican territory, Reily's report was again misleading. According to Reily, Terrazas replied to the Confederate request by saying that "if ever rendered necessary, your troops will have no trouble." In fact, Governor Terrazas was specific that he could not allow such pursuits to take place. However, he did offer the slight concession that, if and when he judged that the situation warranted it, he would make application to the Mexican Congress to allow such pursuits, and if such application were granted by the Congress, he would then allow it (of course he probably knew of the hostility of the Mexican central government to the Confederacy, and that any application on its behalf would certainly have been denied by the Congress).22

On the third point, the right to purchase and store supplies in Mexico, Reily and Terrazas apparently did reach an agreement. However, the Mexicans would not accept Confederate currency, and since the Confederates lacked any substantial amounts of gold or silver, the accord thus reached was of little practical use to the Confederacy.23

Why did Reily and Terrazas interpret the results of their discussions so differently? There are several possible reasons for this. One possibility is the language barrier. Reily spoke no Spanish, and Terrazas no English, and in the course of translation meaning could have been altered for one or both of them. Another possibility is the deliberate deception of Reily by Terrazas. Terrazas may indeed have VERBALLY assured Reily of his agreement on the concessions requested, and later, in writing, repudiated his verbal agreements. This would seem to be a more likely answer to the mystery at hand. As one historian has stated, Terrazas was "between three fires, the Union, the Confederacy, and Mexico," and it seems likely that he simply chose not to add fuel to one fire for fear of being burned in return by the others.24 And there is one possibility as well. It is not impossible that Reily himself exaggerated the success of his negotiations, either out of the incorrigible enthusiasm which was a feature of his personality, or as a deliberate attempt to ingratiate himself with his commander. In either case, the letter sent by Terrazas to Sibley would have revealed Reily's exaggerations for what they were.

Captain Sherod Hunter

After returning from Chihuahua, Colonel Reily was ordered to proceed to Hermosillo, the capital of Sonora. He accompanied Captain Sherod Hunter's command when it left Mesilla, capital of the Confederate Territory of Arizona, for the little adobe village of Tucson on February 14, 1862.25 Arriving in Tucson on February 28th, Reily participated in the flag-raising ceremony in the town plaza, whereby Captain Hunter formally took possession of Tucson (and western Arizona) for the Confederacy. Reily made a speech that was well-received by the crowd.26 On March 3rd he left with his escort (20 men commanded by Lieutenant James H. Tevis) to proceed on to Sonora.27

Don Ignacio Pesqueira, Governor of Sonora

Upon arriving in Sonora, Reily was received at the palace of Governor Don Ignacio Pesqueira. Reily here bargained for the same concessions he had sought in Chihuahua, and it seems that he apparently did in fact enjoy success with the Governor of Sonora. Pesqueira verbally assured Reily that Sonora would forbid the use of the port of Guaymas to the United States, refuse the Union Army transit over its territory, grant free entry and passage to the Confederate Army, and supply the Confederates with food and military stores. Pesqueira also stated that not only would Sonora agree to these concessions, but the province would rebel from the Republic if the Juarez government questioned its authority to do so. It is possible that the future annexation of Sonora by the Confederate States was also discussed, but if so, the results of that discussion have not been recorded.28

Unfortunately for Reily and for Confederate hopes, there was in Hermosillo at that time an enterprising reporter for the SAN FRANCISCO BULLETIN, one W. G. Moody. Moody heard of the discussions between Reily and the Governor, and he managed to steal copies of Reily's introduction from Sibley and some of his notes (Moody stole the letters from the office of Pesqueira's translator, when the latter left to take the Spanish copies to the Governor) and transmit them to General Wright, the commanding General of Union forces in California. Within days, Wright had a gunboat on patrol off the harbor at Guaymas. He also had a letter prepared and sent to Pesqueira, containing what historian Robert Lee Kerby has called "one of the most diplomatic threats ever penned."29

Wright's letter started off by congratulating Pesqueira for REFUSING Reily's overtures. Wright then went on to assure the Mexican official that "under no circumstances will the Government of the United States permit the rebel hordes to take refuge in Sonora. I have an army of ten thousand men ready to pass the frontier and protect your government and people." Upon receiving Wright's "promise of protection," Pesqueira suddenly decided to to reconsider his accord with Reily. He sent a letter to General Sibley, stating that Reily's claims of success had been "exaggerated, or perhaps badly misinterpreted." And as a final indignity, in August 1862 (after Sibley's army had been defeated and the Confederate position in Arizona had collapsed), Pesqueira sent a letter to General Wright promising that if any "rebels" set foot on Mexican soil, he would exterminate them. Thus ended James Reily's mission to Sonora.30

In the end, perhaps the only "achievement" of Reily's missions to Chihuahua and Sonora was the "recognition" of the Confederacy as a nation by the Governors of those states. Reily was presented to the Governors of both States while wearing the uniform of a Colonel of Cavalry, Confederate States Army. He insisted on being addressed by his title, and always negotiated on the understanding that he represented a sovereign nation. And both Governors, Terrazas and Pesqueira, did negotiate with him on that basis. Of course that leaves open the question of whether recognition of the Confederacy as a legitimate nation by the governors actually represents "recognition by a foreign power" under international law. The central government of Mexico never recognized the Confederacy, and it is uncertain whether states in a federal system of government, even if virtually independent of the control of the central government (as Chihuahua and Sonora were in the 1860s), can independently recognize a foreign nation. All thi writer can say is that Reily thought so!31

With the end of the diplomatic missions of James Reily to Sonora and Chihuahua, and especially after the collapse of the Confederate Territory of Arizona, Confederate aspirations in Mexico dwindled away into nothing. Eventually the affair would be virtually forgotten, even by historians. Yet the Confederate attempt to annex the northern provinces of Mexico was an important episode in the history of the War Between the States. If the Confederates had been successful, the advantages gained might have shifted the balance of power in their favor, and their struggle for independence might have had a different outcome. For this, if for no other reason, the story of Confederate diplomacy and intrigue in Mexico deserves to be told.

NOTES

1

Robert Lee Kerby, THE CONFEDERATE INVASION OF NEW MEXICO AND ARIZONA, 1861-1862, Los Angeles, California: Westernlore Press, 1958, pp 48-49. Hereafter cited as Kerby; Brigadier General Latham Anderson, "Canby’s Services in the New Mexico Campaign," BATTLES AND LEADERS OF THE CIVIL WAR, Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, Ed., New York: Century, 1883-1888, Volume II, pp 697-698. Hereafter cited as Anderson.2

Anderson, pp 697-698.3

Trevanion T. Teel, "Sibley’s New Mexican Campaign: It’s Objects and the Causes of It’s Failure," BATTLES AND LEADERS OF THE CIVIL WAR, Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, Ed., New York: Century, 1883-1888, Volume II, p. 700. Hereafter cited as Teel.4

Teel, p. 700.5

Kerby, pp 46-47.6

Kerby, p. 47.7

James Farber, TEXAS, C.S.A.: A SPOTLIGHT ON DISASTER, New York: The Jackson Company, 1947, pp 118-120. Hereafter cited as Farber.8

Kerby, p. 47; Farber, pp 118-120.9

Kerby, p. 47; Farber, pp 118-120.10

Farber, pp 120-121.11

Kerby, 47-48.12

Kerby, p. 43.13

Details of Quintero’s life are from Clement A. Evans, Ed., CONFEDERATE MILITARY HISTORY EXTENDED EDITION: A LIBRARY OF CONFEDERATE STATES HISTORY, WRITTEN BY DISTINGUISHED MEN OF THE SOUTH, Wilmington, North Carolina: 1988 (reprint of 1899 edition), Volume XIII--Louisiana, pp 556-557.14

Kerby, pp 43-44.15

Letter from Brigadier General Henry Hopkins Sibley to General Samuel Cooper, January 3, 1862, reprinted in Calvin P. Horn and William S. Wallace, CONFEDERATE VICTORIES IN THE SOUTHWEST: PRELUDE TO DEFEAT, Albuquerque, New Mexico: Horn and Wallace, 1961, p. 118, hereafter cited as Horn and Wallace.16

The first 3 goals can be inferred from a letter from Col. James Reily to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 20, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, pp 123-125, in which Reily describes the content of his negotiations with Governor Luis Terrazas of Chihuahua.17

Kerby, p.60.18

Farber, p. 122.19

Letter from Col. James Reily to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 20, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, pp 123-125.20

Letter from Col. James Reily to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 20, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, pp 123-125.21

Letter from Col. James Reily to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 20, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, p. 124; Letter from Governor Luis Terrazas to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 11, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, pp 122-123.22

Letter from Col. James Reily to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 20, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, p. 124; Letter from Governor Luis Terrazas to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 11, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, pp 122-123.23

Letter from Col. James Reily to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 20, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, p. 124; Letter from Governor Luis Terrazas to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 11, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, pp 122-123.24

Kerby, p. 62.25

Orders from Lt. Col. John R. Baylor to Captain Sherod Hunter, February 10, 1862, found in the Sherod Hunter "Jacket" at the National Archives, Washington, D.C.26

L. Boyd Finch, "The Civil War in Arizona: The Confederates Occupy Tucson," ARIZONA HIGHWAYS, January 1989, p. 17; Kerby, p. 78.27

Captain Sherod Hunter, report to Lt. Col. John R. Baylor, April 5, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, pp 200-201.28

Kerby, p. 79.29

Kerby, p. 80.30

Kerby, p. 80.31

Letter from Col. James Reily to Brigadier General Henry H. Sibley, January 20, 1862, reprinted in Horn and Wallace, pp 120-121; Farber, p. 122; Kerby, p. 61.

![]()

Some clipart on this page was used courtesy of

and

The music file of "The Southron's Chaunt of Defiance" was composed and is copyrighted by Benjamin Tubb. For more of his great tunes, visit his website, THE MUSIC OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR. Great, ain't it?

The author is also endebted to Ron Terrazas, who provided a correction to the information about Don Carlos Moye, brother-in-law of Governor Luis Terrazas of Chihuahua; and to Gustavo Carmona, who provided pictures and information about Governor Baylor's spy in Sonora and Chihuahua, Jose Augustin Quintero.

![]()

BACK

TO THE ARIZONA CONFEDERATES PAGE

BACK

TO THE ARIZONA CONFEDERATES PAGE

Copyright 2000-2007 by the Colonel Sherod Hunter Camp 1525, Sons of Confederate Veterans, Phoenix, Arizona. All rights reserved. Last updated on 23 July 2007.

CHARGE

AHEAD TO THE NEXT PAGE

CHARGE

AHEAD TO THE NEXT PAGE